BBMRI.at Legal Knowledge Base

Legal Q&A: What are my donor’s rights? Are my data safe? How is handling with data regulated?

The session explored data protection concerns related to biobanking, with a focus on sample donors’ rights under European Union law—particularly the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)—as well as Austrian legal frameworks.

BBMRI.at Legal Helpdesk answers

The BBMRI.at Legal Helpdesk Service – operated by legal experts from BBMRI.at partner UNIVIE- answers questions on legal and regulatory matters around biobanking and/or using biological samples and data. This service is offered to BBMRI.at partners to support them, as biobanking and research using biological samples and data (e.g. human, animal/veterinary, microbial, etc.) may raise legal questions. Answers provided by UNIVIE to legal questions are published in the BBMRI.at Knowledge Base.

QUESTION:

Legal Q&A: Biobank donor rights, data safety, and data regulations

ANSWER:

1. Data Protection in the GDPR

Individuals who chose to donate their biological samples to biobanks are holders of rights with regards to the personal data (Article 4(1) of the General Data Protection Regulation[1], hereinafter: GDPR) – and, more specifically, data concerning health[2] – which are intertwined with the sample provided to the biobank. Therefore, sample donors are simultaneously data subjects, whose rights are protected by the existing European Union (hereinafter: EU) legal framework for data protection (of which the GDPR is a prime example[3]) and national legal instruments that coexist which the EU framework. In Austria, such legal acts are, for example, the Forschungsorganisationsgesetz, (Austrian Research Organisation Act, known as FOG[4]) and the Datenschutzgesetz, Austria’s Data Protection Act, commonly referred to as DSG[5]). Their data must therefore be handled in accordance with the currently applicable legal requirements.

As covered in Question no. 18, a biobank seeks permission, from the sample donor, upon provision of sufficiently detailed and accurate information, to collect their sample, store it for an agreed to timeframe and process it for the consented to purposes. Simultaneously, as regards to the personal data connected or processed from the sample, the GDPR stipulates that consent[6] may serve as the legal basis for processing[7] the personal data (Article 6(1)(a), Article 9(2)(a)) and should also be preceded by the provision of certain information to the data subject (Article 7(3))[8]. A data subject is allowed to withdraw their consent at any time[9].

Within the context of the GDPR, biobanks can likely be described, in most circumstances[10], as data controllers, i.e., as they determine the purposes and means of the processing of personal data[11]. As such, they are required to fulfil certain obligations (as set out within the GDPR, Articles 25 and ff.) that are designed to protect the rights of the sample donors as data subjects, such as seeking their consent for personal data processing, or otherwise identifying another legal basis for processing their personal data[12]. A biobank, when deemed a controller, is also responsible for proving that adequate consent has been sought from the data subject: Article 7(1) of the GDPR regarding personal data processing, states that “[…] the controller shall be able to demonstrate that the data subject has consented to processing of his or her personal data” (emphasis added). In fact, the biobank, as controller, has a general duty of accountability, i.e., it is responsible for, and must be able to demonstrate compliance with Article 5(1) of the GDPR (which describes the principles relating to processing of personal data).

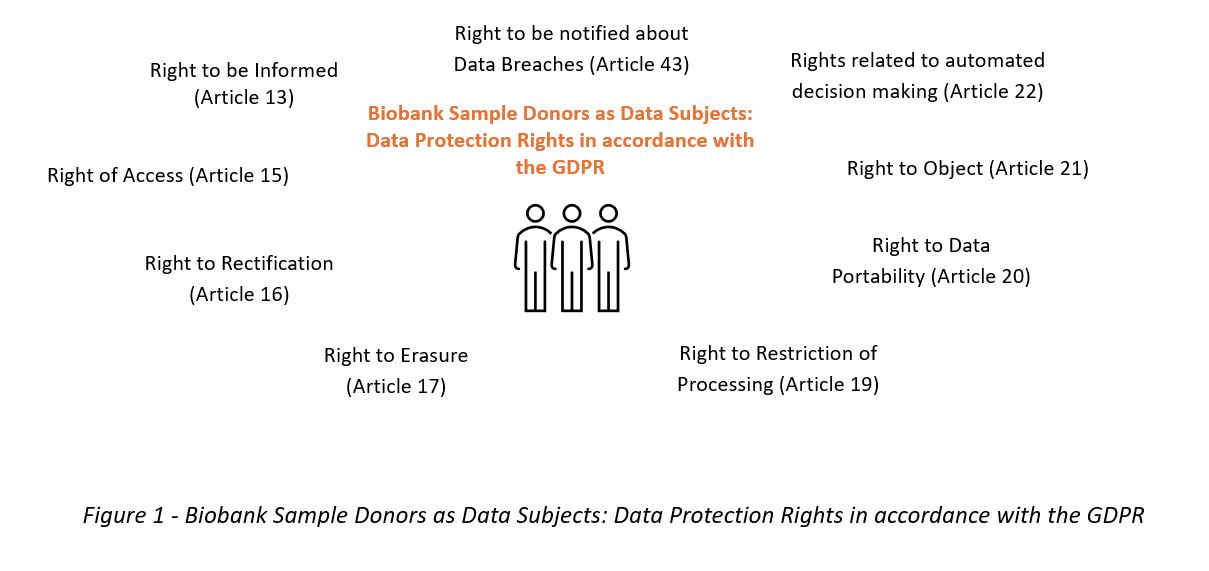

Additionally, as data controllers, biobanks are the main guarantors of data protection rights that the GDPR endows data subjects with. These rights (enunciated in Figure 1) are heavily intertwined with the aforementioned principles of processing personal data which are included in Article 5(1) of the GDPR: (1) lawfulness, fairness and transparency; (2) purpose limitation; (3) data minimisation; (4) accuracy; (5) storage limitation; and (6) integrity and confidentiality.

In summary, sample donors subject to the provisions of the GDPR know that[13]:

- there is a legal basis for processing their data (principles of lawfulness, fairness and transparency, as described in Article 5(1)(a)). Should consent be the legal basis for processing data, it should be preceded by the provision of relevant information. Information includes, inter alia,[14] information about the data subject’s legal right to withdraw consent at any time. This is a derivation of the principle of lawfulness and the data subjects’ right to information, which extends beyond the information necessary for the provision of consent (i.e, “[…] the right to information should not be confused with informed consent”[15]). The right to information is intrinsically linked to the right to data portability (Article 20). Additionally, data subjects may request access (right of access) to this information in accordance with Article 15 of the GDPR. If the lawful basis of processing is either public interest (Article 6(1)(e)) or legitimate interests (Article 6(1)(f)), data subjects are also entitled to exercise the right to object to the processing of their data in accordance with Article 21 of the GDPR. Key articles: Articles 5, 6, 7, 13, 15, 20 and 21.

- their personal data can only be processed for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes. This is in line with the principle of purpose limitation. Further processing, i.e., processing for a “[…] purpose other than that for which the personal data were collected […]” (Article 13(3)), is only permitted in very specific circumstances (Article 5(1)(b)). When such further processing is due to take place, data subjects are necessarily made aware of that intention (Article 13(3)). Key articles: Articles 5 and 13.

- the personal data collected by the biobank are “adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which they are processed […]” (Article 5(1)(c) of the GDPR). The biobanks should also ascertain whether the purpose of the processing could not reasonably be fulfilled by other means (Recital 39 GDPR) (adequacy). Key article: Article 5.

- the personal data provided are accurate and can be rectified, at the discretion of the data subject, whenever required. The duty of keeping accurate information burdens the biobank (Article 5(1)(d)) and endows the data subjects the right of rectification and erasure (Articles 16 and 17). The data subjects may also request to exercise their right to restriction of processing when the accuracy of the data in question is contested (Article 19). Key articles: Articles 5, 16, 17 and 19.

- once the personal data collected are no longer necessary for achieving the original purposes, they will be anonymised or erased. This is a duty under the principle of storage limitation (Article 5(1)(e)). In line with the right to be informed, the data subjects will be informed of the duration of the storage of the data (Article 13(2) and Article 14(2)) and may also request to exercise their right to restriction of processing when the data are no longer needed for the original purpose but may not be deleted due to legal requirements (Article 19). Key article: Article 5.

- the data are protected against unauthorised or unlawful processing, as well as accidental loss, destruction or damage, through the use of appropriate technical or organisational measures (Article 5(1)(f)). In the event of a data breach, data subjects are informed in accordance with Article 43 of the GDPR. This means that there are measures implemented to keep the data subjects’ data safe. Key articles: Articles 5 and 13.

- they have the right, pursuant to Article 22 of the GDPR, to not be subject to a decision based solely on automated decision making, which includes profiling, if this produces legal effects on the data subject, or significantly affects them. Key article: Article 22.

- biobanks, if deemed data controllers, are responsible for, and must be able to demonstrate compliance with paragraph 1 of Article 5 of the GDPR. Data subjects are informed about “the identity and the contact details of the controller and, where applicable, of the controller’s representative” (Article 13(1)(a)). In those cases where a data protection officer exists, their contact details are also made available to the data subjects (Article 13(1)(b)). Key articles: Articles 5 and 13.

- the monitoring of the application of the GDPR falls both on independent public authorities in each Member State (Articles 51 and 57). The data subjects can resort to lodging a complaint with a supervisory authority pursuant to Article 77, to other available administrative or non-judicial remedy or exercise their right to an effective judicial remedy if they consider that their rights under this GDPR have been infringed as a result of the processing of their personal data in non-compliance with the Regulation (Article 79). Key Articles: 51, 57, 77 and 79.

2. Data Altruism

Another point of specific interest to data subjects who are donors of samples for biobanking activities is the concept of data altruism. The Data Governance Act[16] (hereinafter: DGA), “”[…] seeks to facilitate further sharing of personal data by introducing a concept of data altruism”[17], defined as “[…] the voluntary sharing of data on the basis of the consent of data subjects to process personal data pertaining to them, or permissions of data holders to allow the use of their non-personal data without seeking or receiving a reward that goes beyond compensation related to the costs that they incur where they make their data available for objectives of general interest as provided for in national law, where applicable, such as healthcare, […] or scientific research purposes in the general interest” (Article 2(16), emphasis added). For sample donors and biobanks, the provisions regarding data altruism consubstantiate a mechanism which can be considered interesting to, inter alia, streamline the process of obtaining consent to process personal data (including data concerning health: Article 3 of the DGA, a contrario) to pursue these scientific purposes. This is possible because the DGA provides that the European Commission is due to produce a standard consent form for data altruism[18].

This may help biobanks overcome the different national law implementations of the GDPR, particularly with regard to consent and its use as legal basis for scientific research[19]. Issues pertaining to consent already covered by the GDPR[20], such as the data subjects’ right to withdraw their consent (albeit from “a specific data processing operation”, which does not coincide with the wording of Recital 33 of the GDPR and Recitals 26 and 50 of the DGA, which refer to the consent given to “certain areas of scientific research”) are included in the DGA. Concerns such as having forms be “easily understandable” (Article 25(4) of the DGA) are very much in line with transparency considerations within the GDPR (Recitals 39, 58 and Article 5(1)(a)).

Sources:

[1] General Data Protection Regulation: Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation).

[2] Within the meaning of Article 4(15) of the GDPR

[3] The territorial scope of the GDPR, as described in Article 3 of the Regulation, means that biobanks established in the EU (Recital 22) who take up Personal Data processing activities (which includes, in accordance with Article 4(2) of the GDPR, a broad range of processing operations such as “[…] collection, recording, organisation, structuring, storage, adaptation or alteration, retrieval, consultation, use, disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available, alignment or combination, restriction, erasure or destruction”) are required to fulfil data protection obligations which derive from the GDPR.

[4] Bundesgesetz über allgemeine Angelegenheiten gemäß Art. 89 DSGVO und die Forschungsorganisation (Forschungsorganisationsgesetz – FOG), StF: BGBl. Nr. 341/1981. 09/07/2024).

[5] Bundesgesetz zum Schutz natürlicher Personen bei der Verarbeitung personenbezogener Daten (Datenschutzgesetz – DSG) StF: BGBl. I Nr. 165/1999.

[6] Article 4(11) of the GDPR.

[7] Article 4(2) of the GDPR.

[8] For an overview on the topic of informed consent, vide: Cippitani, R. (2023). Consent Requirements: What Are the Terms and Conditions of Informed Consent?. In GDPR Requirements for Biobanking Activities Across Europe (eds. Valentina Colcelli / Roberto Cippitani / Christoph Brochhausen-Delius / Rainer Arnold). Springer International Publishing, pp. 97-108.

[9] Article 7(3) and Recital 65 of the GDPR.

[10] As described by authors, “Whether or not biobanks assume the roles of data controllers and/or data processors for GDPR compliance purposes will largely depend on their actual functions, manner of operating and whether the specific tasks can be considered data processing of personal data”, in: Nordberg, A. (2021). Biobank and biomedical research: responsibilities of controllers and processors under the EU General Data Protection Regulation. GDPR and Biobanking: Individual Rights, Public Interest and Research Regulation across Europe, pp. 61-89, p. 62.

[11] GDPR, Article 4(7).

[12] Articles 6 and 7 of the GDPR.

[13] A detailed description of individual rights in the context of biobank research can be found in Staunton, Ciara (2021). Individual Rights in Biobank Research Under the GDPR. GDPR and Biobanking: Individual Rights, Public Interest and Research Regulation across Europe, pp. 91-104.

[14] Forgó, N., Kollek, R., Arning, M., Kruegel, T., & Petersen, I., (2010). Ethical and Legal Requirements for Transnational Genetic Research. C.H. Beck, Hart, Nomos, pp. 30-31.

[15] Staunton, Ciara (2021), Op. Cit., p. 93.

[16] Regulation (EU) 2022/868 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2022 on European data governance and amending Regulation (EU) 2018/1724 (Data Governance Act) (Text with EEA relevance). The DGA entered into effect on the 23rd June 2022 (and became applicable in September, 2023 – Article 38 of the DGA) and is one of the new legal instruments that shall provide solutions to the availability of data, imbalances of market power, data governance, interoperability and quality problems as described in the “European strategy for data”, published in February 2020.

[17] Ruohonen, J., & Mickelsson, S. (2023). Reflections on the data governance act. Digital Society, 2(1), 10.

[18] Recital 52 and Article 25 of the DGA.

[19] This is partially covered by the answer provided to Question no. 18.

[20] Which will remain unaffected: Article 1(3) of the DGA.

Disclaimer: this commentary aims to provide a summary of the main ethical and legal issues related to the questions put by interested stakeholders and to direct them to the relevant legal provisions that are applicable. It does not, however, preclude from reading the official sources of legislation relating to the subject matters of this document as well as those quoted by the authors and does not constitute legal advice.